Education as a Catalyst for Conservation in Madagascar

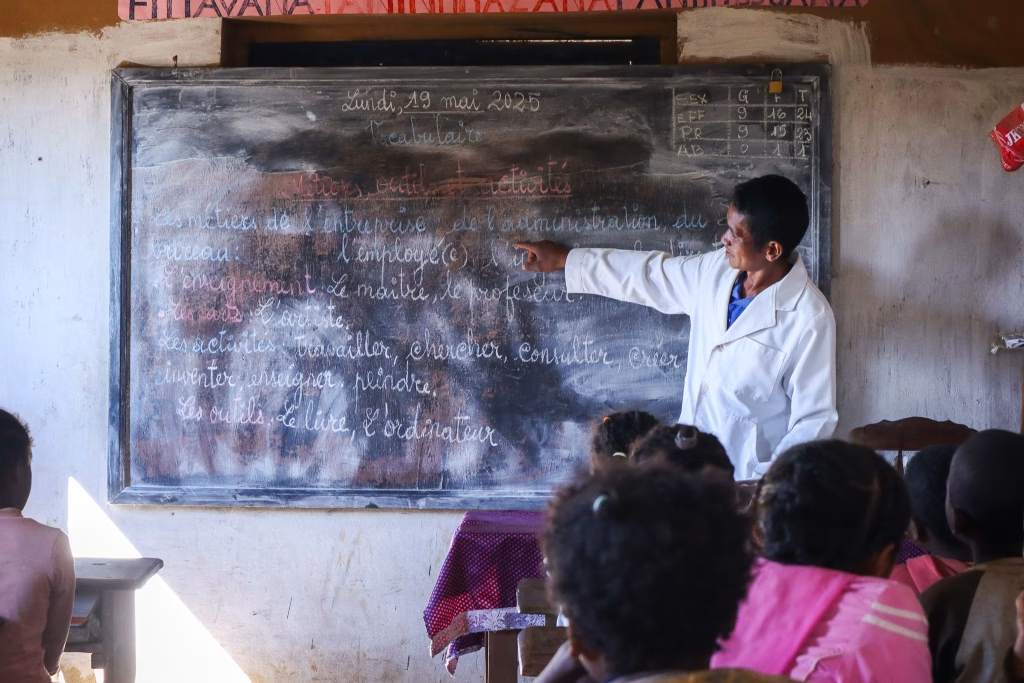

In Madagascar, education is not just a human right—it is a conservation imperative. The island has a remarkable diversity of wildlife. Approximately 96 percent of Madagascar’s reptiles, 90 percent of its plant life, and 95 percent of its mammals exist nowhere else on Earth (Goodman 2023). There are over 110 species of lemurs that are found nowhere else on our planet, and they’re vanishing due to widespread deforestation and unsustainable land-use practices. A surprising number of Malagasy children and adults are unfamiliar with their island’s exceptional biodiversity, including the lemurs¹. This major disconnect stems from deep-rooted challenges: inadequate school infrastructure, lack of biodiversity content in national curricula, and limited or no access to education, especially in rural areas.

According to UNICEF2, the proportion of Malagasy children not attending school in rural areas is twice as high as that of non-attending youth from urban areas. Schools are often situated very far from the communities’ living areas, making the daily commute difficult and dangerous, if not impossible, for many children. In addition to this geographical barrier, there is a socio-economic one: many families face a low standard of living and often cannot afford school fees or books and supplies.

Nature also presents challenges. With Madagascar experiencing several cyclones a year, the natural environment and all human infrastructure (including schools) are vulnerable to natural disasters and climate change (The World Bank, 2020). Schools constructed from locally harvested materials are not strong enough to withstand many of these storms.

The Challenges to Education Are Stark

Wildlife Madagascar has four field sites: La Mananara (a privately-owned forest concession within the Anjozorobe-Angavo Protected Area, Tsingy de Namoroka National Park, Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve (ASSR), and the northern sector of Tsitongambarika Protected Area (i.e., TGK3). The socio-economic survey conducted at ASSR demonstrated that the area’s illiteracy rate is 88%, and fewer than half of the children have access to a school. Where schools do exist, they often lack electricity, books, or even basic supplies, and they often have had no maintenance in years. Other challenges include teachers who do not regularly receive their salaries and families that are unable to afford school fees or are forced to prioritize subsistence farming over formal education. For conservation efforts to succeed, we must provide both children and adults, especially in the rural areas in which we work, with opportunities to learn, grow, and participate in protecting their natural heritage.

The Environmental Challenges Are Also Daunting

Continued losses of wildlife, forests, habitats, and human livelihoods create a spiral of environmental degradation that can only lead to tragedy. Rural communities have been experiencing significant population growth, but have little to no access to economic opportunities. The result has been overexploitation of wildlife species, deforestation, and agricultural practices that negatively impact soil and water resources.

These habitat encroachments have been triggered by several interconnected root causes, including the increased demand for hardwoods, the need of local communities for immediate income due to lack of food security, a lack of understanding of the role an intact forest has on long-term livelihoods (i.e., ecosystem services), the challenges faced due to fires set for land clearing, and a lack of access to the most beneficial and successful farming practices or the proper varietals for the region.

The Strategy and Goals

Wildlife Madagascar’s education strategy is grounded in the belief that fostering empathy for local wildlife and pride in biodiversity begins with an education program that is relevant, inclusive, and community driven. If implemented with care and community collaboration, this strategy has the power to transform. Local families will gain skills and knowledge that will improve livelihoods and reduce pressure on protected areas since they will obtain food security. Furthermore, the economic standing of communities and the country will improve. Youth will grow into conservation-minded leaders, and communities will become stewards of the forests that help sustain them. In time, this model can ripple outward by building a generation of Malagasy who know and care deeply for their island’s forests and who will pass on their knowledge and skills to the next generation.

Our goals include making education accessible and impactful in even the most remote communities, creating conservation advocates among the next generation, and providing adult education programs that address the root causes of deforestation, primarily through training in sustainable agriculture.

To address the considerable need for educational services in the communities in which we work, our education strategy has six main objectives.

1. Building Learning Hubs for Community and Environmental Resilience

2. Farming for a Food-Secure and Forest-Safe Future

3. Cultivating Local Youth to Lead the Future

4. Fostering a Culture of Conservation Through Education

1. Building Learning Hubs for Community and Environmental Resilience

Objective: By December 2030, construct or rehabilitate 10 schools across Wildlife Madagascar’s four field sites—La Mananara, Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve (ASSR), Namoroka National Park, and Tsitongambarika (TGK3). Each will be equipped with student desks, teacher supplies, solar lighting, a basic library, and internet to serve at least 3,000 students annually.

Program Description: In many of the communities where Wildlife Madagascar operates, access to quality education is extremely limited or nonexistent. For example, in the communities surrounding ASSR, fewer than half of the children have access to a school, and those who do often attend classes in poorly maintained buildings without electricity, furniture, or educational materials. In some villages, classes are held outdoors or in temporary shelters. Without schools, communities are deprived of one of the most powerful tools for breaking the cycle of poverty and environmental degradation.

We plan to address the acute need for educational infrastructure by building or rehabilitating 10 schools strategically located in areas where the need is greatest—where the fewest schools exist and where the fewest children have access—and where the conservation impact will be maximized. These schools will serve as dual-purpose learning hubs—providing formal education for children during the day and hosting adult agricultural and ecotourism training in the evenings and on weekends. Each school will be equipped with:

- Durable student desks and teacher furniture

- Chalkboards and basic teaching supplies

- A starter library with books in Malagasy, French, and English

- Educational materials about local wildlife and ecosystems

- Solar panels to ensure basic lighting

- Clean water access (where feasible)

- Internet access

- Computer

Wildlife Madagascar will also provide a conservation and biodiversity curriculum and teacher training, creating a foundational understanding of the value of the island’s unique natural heritage from an early age. The ultimate vision is not only to improve access to education but also to create future conservation leaders and stewards of Madagascar’s forests.

Implementation Plan

2. Farming for a Food-Secure and Forest-Safe Future

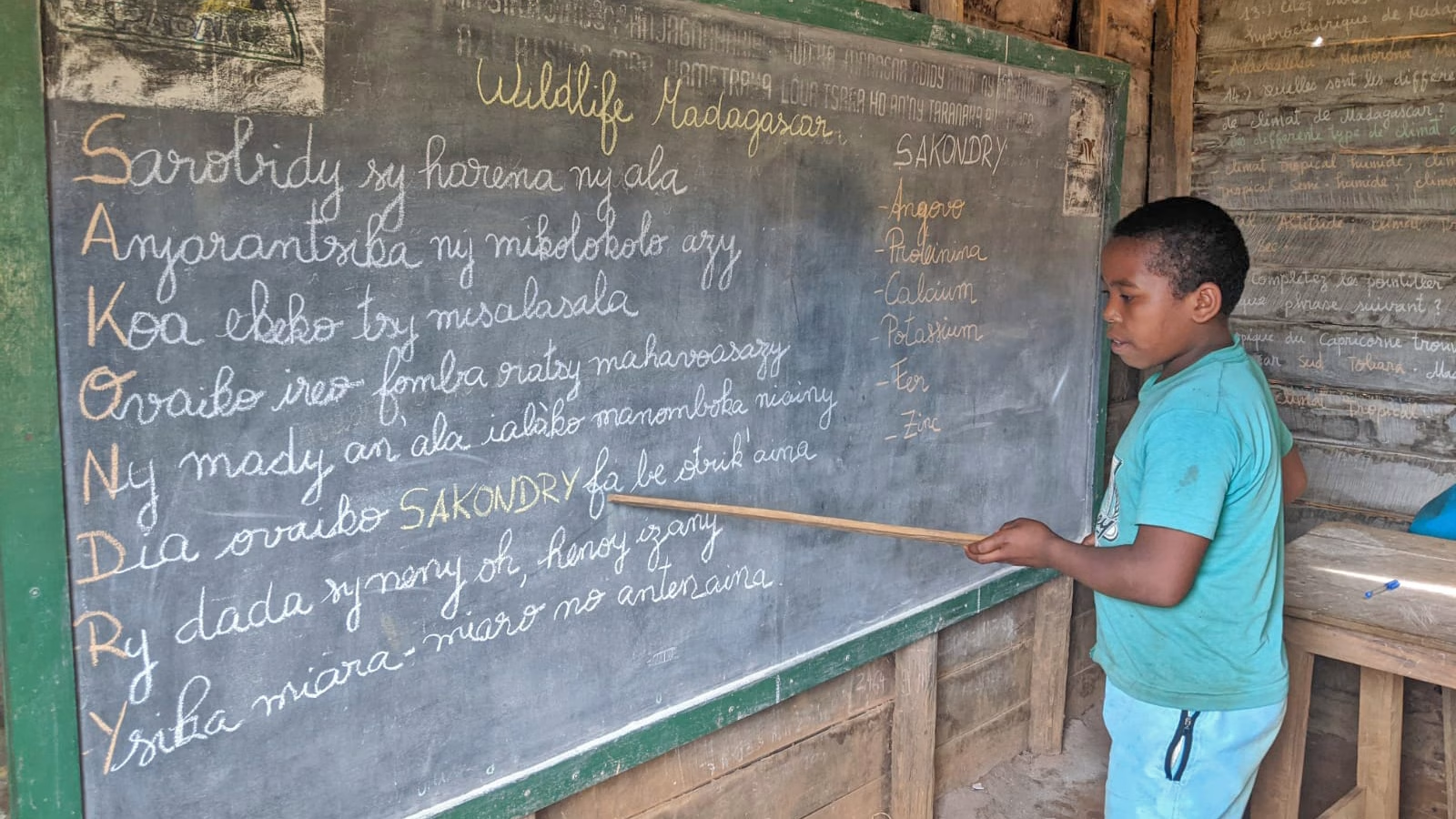

Objective: By December 2029, launch formalized agricultural training programs for adults at each of Wildlife Madagascar’s four field sites—La Mananara, Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve (ASSR), Namoroka National Park, and Tsitongambarika (TGK3)—focused on fire-safe, sustainable agriculture, community and household food gardening, and sakondry (edible insect) farming. The goal is to improve food security for at least 300 households per site, generating income and reducing pressure on animals and plants living in local forests. At least 60% of participants will adopt one or more new conservation-aligned practices within six months of completing training.

Program Description: In many of the rural communities where Wildlife Madagascar operates, environmental degradation is a direct consequence of economic hardship and food insecurity. Communities often rely on slash-and-burn agriculture (tavy), overgrazing, illegal logging, and bushmeat, not from a lack of concern for the environment but from a lack of viable alternatives. Our agricultural training program addresses those needs by equipping adults, especially farmers, herders, and youth entering the workforce, with practical, low-cost, and culturally appropriate techniques that improve food security and reduce ecological impact.

Key program elements include:

- Sakondry Farming: Cultivating a culturally accepted, climate-friendly protein source through sakondry farming

- Community Gardens: These demonstration gardens will serve as hands-on training sites and sources of inspiration for local families. They will showcase sustainable growing practices, including composting, with their produce used to support meals for schoolchildren and visitors, while encouraging households to start their own food gardens

- Sustainable Household Gardening: Growing diverse, nutritious crops using composting, soil restoration, and water management strategies

- Fire-safe Agricultural Practices: Promoting alternatives to tavy and training in safe burning techniques such as firebreak creation, seasonal timing, and no-burn soil fertility methods

- Agroecological Principles: Emphasizing forest-friendly land use, erosion control, crop rotation, and permaculture principles adapted to local conditions

These trainings will be delivered in Malagasy using illustrated manuals, participatory methods, and hands-on demonstration sites tailored for low-literacy learners. Each training site will include a community demonstration garden which will be open to participation by all students and all local residents.

Implementation Plan

3. Cultivating Local Youth to Lead the Future

Objective: By April 2026, launch a needs-based scholarship program that provides full support (tuition, supplies, transportation, and meals) to at least 16 high-performing students per year.

Program Description: In rural Madagascar, even when schools are physically available, many children cannot afford to attend due to the cost of uniforms, supplies, and meals—or because they are needed at home to help with farming or household duties. This is especially true in the rural communities surrounding Wildlife Madagascar’s four field sites, where poverty rates are among the highest in the country. Without support, many bright and motivated students are forced to abandon their education, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and limiting the emergence of local conservation champions.

Wildlife Madagascar’s scholarship program will directly address this barrier by providing targeted support to academically strong, conservation-minded students from under-resourced families. Scholarships will cover:

- Uniforms and school supplies

- Transportation (when necessary)

- Daily school meals

- Mentorship

- Participation in special, targeted programs

The program will focus on merit and need, ensuring that both academic promise and financial hardship are considered in the selection process. It will also be inclusive, with an emphasis on gender balance and support for students from communities that border our field sites.

Implementation Plan

4. Fostering a Culture of Conservation Through Education

Objective: By the end of 2028, deliver flexible, conservation-themed education programs in at least 50 classrooms and 15 community centers across Wildlife Madagascar’s four field sites, reaching 5,000 children and adults per year, with pre-and post-program surveys used to measure changes in knowledge, attitudes, and conservation behaviors.

Program Description: Most students in rural Madagascar have little to no exposure to Madagascar’s unique wildlife or the environmental issues threatening it—despite living at the forest’s edge. At the same time, many adults are disconnected from formal education opportunities and rely heavily on natural resources for survival, often without access to sustainable alternatives.

This program seeks to embed conservation education into the daily lives of both children and adults through flexible, place-based programs designed for classrooms, community centers, and informal gathering spaces. These programs will use age-appropriate content, interactive methods, and real-world examples that connect biodiversity protection to community well-being.

In schools, we will integrate conservation modules into existing lessons—such as science, geography, and even language arts—making it easy for teachers to deliver. In community settings, workshops will be hosted through local associations, women’s cooperatives, and village events, and will focus on sustainability topics directly tied to everyday life, such as forest-friendly farming, waste management, and human-wildlife coexistence.

The program will be grounded in Madagascar’s cultural values, with materials that reflect local traditions, stories, and conservation heroes. It will also promote pride in Madagascar’s natural heritage and empower communities to become active stewards of their environment.

Implementation Plan

5. Creating Malagasy Conservation Educators

Objective: Train 100 educators and community leaders across Wildlife Madagascar’s four field sites by the end of 2027 in conservation education methods, including interactive and low-resource teaching strategies, with at least 80% demonstrating improved conservation knowledge on post-training assessments.

Program Description: Teachers and community educators are among the most influential voices in rural Madagascar, yet few have access to conservation education resources or formal training in environmental science. Without this knowledge, even the most dedicated educators cannot introduce students to the importance of Madagascar’s unique wildlife or the role their communities play in protecting forests, water sources, and biodiversity.

This program aims to equip 100 teachers and community educators—across primary and secondary schools, adult education programs, and informal community platforms—with the knowledge, tools, and confidence to lead engaging, culturally relevant, and science-based conservation education efforts. Special emphasis will be placed on hands-on learning, storytelling, and traditional ecological knowledge to connect conservation to daily life in meaningful ways.

The program will also develop a reusable Conservation Educator Toolkit in Malagasy, French, and English that includes visual aids, activity guides, and mobile friendly materials for remote or resource-limited settings. This toolkit will be distributed alongside in-person training sessions and updated based on teacher feedback.

Implementation Plan

6. Color the World with Chameleon Conservation

Objective: By May 2026, increase the number of participating organizations in International Chameleon Day from 30 to at least 70, double website traffic compared to 2024, and generate at least 200 pieces of user-generated content and 10 media features annually across platforms.

Program Description: International Chameleon Day, founded by Wildlife Madagascar and celebrated each year on May 9, shines a global spotlight on one of Madagascar’s most iconic and threatened reptile groups. In its inaugural year, over 30 partner organizations joined the celebration, sharing educational content, curriculum resources, and social media campaigns with thousands of individuals across multiple continents. As one of the only global events focused on reptiles, International Chameleon Day offers a powerful platform to promote conservation, science education, and the beauty of biodiversity.

This program objective focuses on expanding the reach, depth, and impact of International Chameleon Day by growing strategic partnerships, enriching content offerings, increasing multilingual accessibility, and leveraging media and social platforms to raise awareness. Long term, this celebration is not just a single-day event, but a year-round opportunity to build conservation literacy and drive engagement among educators, students, researchers, zoos, aquariums, and nature lovers around the world.

International Chameleon Day is also a key tool in Wildlife Madagascar’s broader conservation advocacy strategy, inspiring empathy for underrepresented species and connecting local and global audiences to Madagascar’s forests.

Implementation Plan

References

- 1Conservation Education in Madagascar: Three Case Studies in the Biologically Diverse Island-Continent, by Francine L. Dolins et al., published in the American Journal of Primatology, 2010.

- 2UNICEF Innocenti – Global Office of Research and Foresight, Ministry of Education of Madagascar and UNICEF Madagascar. Data Must Speak: Unpacking Factors Influencing School Performance in Madagascar. UNICEF Innocenti, Florence, Italy, 2023.

- WWF (2024) Living Planet Report 2024 – A System in Peril. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

- Goodman, S. M. (2023). Updated estimates of biotic diversity and endemism for Madagascar—revisited after 20 years. Oryx, 57(5), 561-565.