A Peculiar Clarity Amidst the Dead

By Cohen Manges

When I first applied to college as an undergraduate, I hadn’t considered studying abroad, nor had I given ecology the time of day. Fortunately for me, during my freshman year, I decided I needed a change of pace, and Swarthmore College, my home institution, has an excellent study abroad program. That’s how the next spring I found myself on the admittedly terrifying journey to somewhere I never would’ve expected: Madagascar. I’d never been out of the United States before, had never even lived outside of my home state of Pennsylvania. So, I picked a country that captivates, that draws people in, and never lets them go… Madagascar!

The stunning views are a story that can almost be captured by an expert photographer, but the feeling of life, of vibrancy? Those you have to experience for yourself. I’d never thought it possible for a place to feel as alive and fresh as Madagascar, but the flora and fauna are like nothing I’d ever seen before, and I doubt I’ll see it again anywhere else in the world.

I studied with the School for International Training (SIT) for two months before joining Wildlife Madagascar at La Mananara. With SIT, I had gotten a taste of the wonders of the Malagasy rainforest, but was left hungry for more, so when the opportunity came to do a month of field research, I came to Wildlife Madagascar looking for another bite. Thanks to Dr. Tim Eppley, Wildlife Madagascar’s Chief Conservation Officer, I was able to conduct a short research project at Wildlife Madagascar’s La Mananara research site, spend valuable time with their amazing team, and was even accompanied by two other Americans from the SIT program.

I witnessed firsthand both the beauty of the wild, unfettered from the demands of tourism, and the devastating effects of tavy (slash-and-burn agriculture) and wildfire that have reduced once pristine forests into hills where nothing but the hardiest grasses can grow. I saw, too, just how hard some local people are working to protect what was left of their home, the forest they love. I was touched by their quest to preserve one of the last mid-altitude rainforests in Madagascar’s central highlands.

I was fascinated by the effects of wildfire on forest composition, a topic that has become all too common of late. So I decided to study forest composition in areas affected by wildfire. La Mananara is the perfect place for this kind of study, since it’s relatively small, once had a homogeneous composition that in some areas has been disrupted by wildfire, and has unparalleled accessibility for each type of forest: pristine endemic forest, secondary burned endemic forest, and secondary invasive forest.

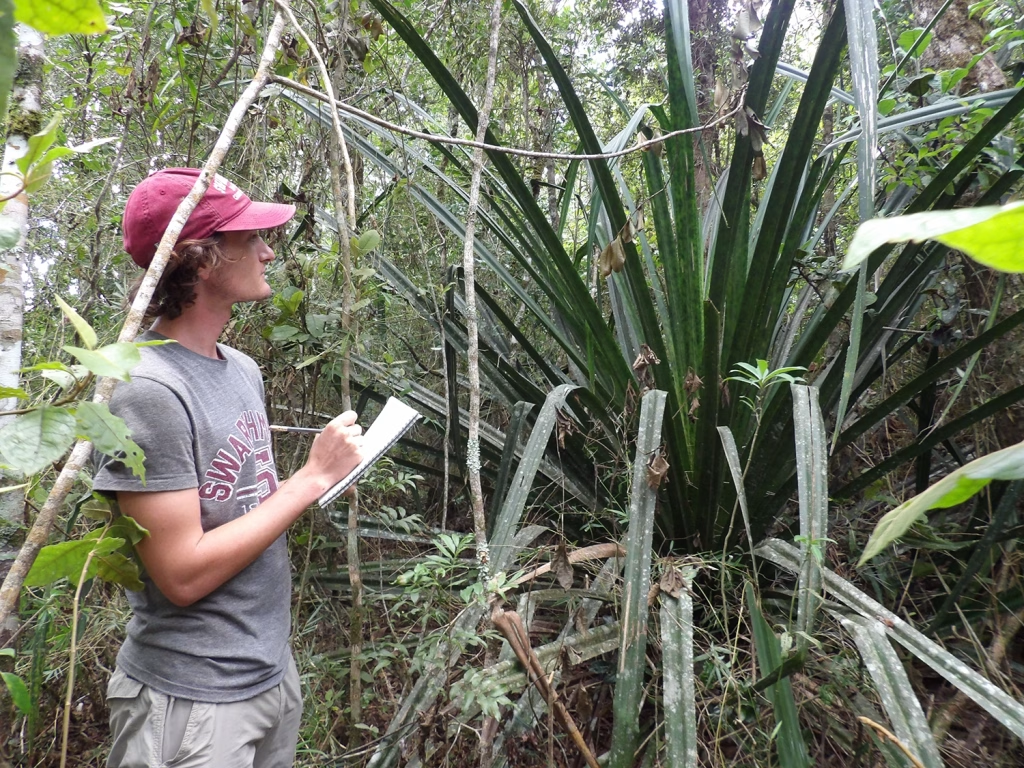

Working with local guides, a visiting botanist, Henintsoa, and occasionally one of the other undergraduate students from SIT, I made a two-kilometer trek into the forest each day to conduct a 0.1-hectare botanical plot, surveying all the trees larger than 10cm in diameter and noting any interesting flora. Every day, staring up at the sun-dappled canopy, I got a fresh wave of incredulity. “How can this be my life?” I wondered. Long gone were the suburban streets I’d grown up on, the squishy bed that I’d grown accustomed to. I’d never even been camping back in the United States, but now I drifted to sleep each night to the soft buzz of insects and woke up to the songs of the indri, Madagascar’s largest lemur. I woke up each morning refreshed and secure in the knowledge that what I was doing mattered.

Understanding compositional changes in the forest might make a tangible difference in the way we approach conservation and reforestation efforts throughout the country. When I walked through the forest with the team, who thankfully knew the paths far better than my directionally challenged self, I didn’t need to quantify how healthy it was. I could feel it; there was something distinctly right about it. Perhaps it was the twittering of the birds, the quiet humming of the insects, the rustling of the leaves high above, perhaps something deep in our evolution that lets us know a place is safe. Then we would leave the pristine forest and enter a recently burned one, and those feelings all went away.

The understory would be choked with thorny vines that pulled at our legs, ripping pants and scratching skin as we clawed our way through a forest with attachment issues. The jarring feeling brought a kind of clarity. The forests of Madagascar, so beautiful, are also incredibly fragile. They’re balanced on the tip of a knife, where one small move, one day of inattention, could cause it all to go up in smoke.

Fortunately for everyone, there were no active wildfires during my month-long stay at La Mananara, so we enjoyed Madagascar’s beauty unspoiled by the imminent threat of destruction. But that’s what makes the work of Wildlife Madagascar so important. Along with the local community, they keep watch to make certain this last bastion of pristine biodiversity remains preserved for future generations, whose right it is to appreciate the natural world as we’ve been given the chance to.